A study which is poorly designed will yield false results at an enormous expense of time and money.

The main aim of clinical studies is to as closely represent the real-world outcomes as possible and the design of the study has a large bearing on whether to accept or reject the null hypothesis. A study which is poorly designed will yield false results at an enormous expense of time and money. On the other hand, data generated from a well-designed study is robust enough to be analysed in multiple ways to give useful insights. Hence, an appropriate design is critical for the clinical study to be meaningful. So what are some of the key parameters that are crucial to a methodically designed study? In this chapter, we list these:

The study objective is the cornerstone around which the trial is developed, and a well-defined research objective is essential to form a hypothesis which can be tested through the study, be it superiority to a placebo control, or non-inferiority to an existing standard-of-care, or equivalence of a generic drug.

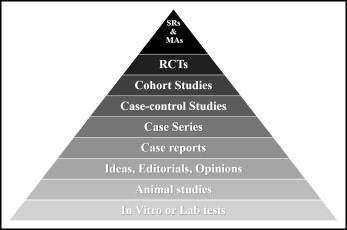

Once the study objective has been described, it becomes easier to determine the type of study which could be employed. Broadly speaking, clinical studies can be categorised as either interventional or observational. As the name suggests, interventional trials are conducted to study the effect of a novel treatment or regimen administered usually in a randomised, double-blind manner and compared against a placebo or standard-of-care control, and include Phase 1-3 clinical trials, detailed in the previous chapter. On the other hand, observational studies which include Phase 4 studies, cohort and case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies deal with issues such as the real-world effects of currently approved interventions, prevalence studies, or disease registries. By and large, the majority of clinical studies conducted are interventional by nature.[1] However, observational studies also play a substantial role in gathering real-world data, identifying patterns and health markers. In evidentiary hierarchy, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) occupy one of the topmost tiers, superseded only by systematic reviews of RCTs (Fig. 1)[2].

Fig 1. The pyramid of evidentiary hierachy [Sackett 1989]

Identification of the target population is of paramount importance to study design. Parameters such as disease indication, gender, age, ethnicity, lifestyle choices and so on need to be defined upfront in order to identify subject eligibility criteria for study enrolment. Consequently, a well-defined list of enrolment criteria assists in effective subject recruitment. The opinion of expert clinicians at the proposed site of the study is indeed valuable in the process, and can in certain instances help speed up the process. On a recent project, we discussed the proposed eligibility criteria of a clinical study with potential researchers and discovered that subjects who would otherwise be excluded were still eligible for enrolment. Our findings helped the client revise the protocol and achieve a more efficient and quicker recruitment, thereby shortening study timelines.

Identification of study procedures is another important aspect of study design since the appropriate evaluation methods will dictate the quality and appropriateness of subject data collected during the course of the study. Given our regularly liaising with the clinical staff, ACT as CRO takes an active role in optimising study procedures for better data acquisition.

The reliability of a study results depends exclusively on the validity and rigour of statistical analysis. Statistical analysis plans are drawn up prior to commencing the study in order to assess study outcomes in an unbiased manner. The sample size needs to be sufficiently large enough in order to identify genuine and statistically significant differences in between tested groups. Too small a sample size reduces the power of the study while too large a number affects the more practical aspects such a study duration, financial and manpower burden, etc. Identification of study outcomes assist in making conclusions and rely on estimating how much difference would be considered to be statistically valid. E.g. the reduction in blood pressure following administration of a new antihypertensive medication or the reduction in glycated haemoglobin values in subjects with diabetes following a regimen with a new insulin. Pre-defining the study outcomes not only helps in distinguishing between true effects and the non-specific ones but also in calculating sample size requisite for a powered study.

Once the preceding steps have been executed, the study design process needs to focus on the more practical aspects of conducting the study. Questions such as the duration of the study, the number of study sites needed to ensure subject recruitments, facilities and infrastructure at the study sites for clinical evaluations required, etc. bear equal importance and need to be addressed when designing a study. Pertinent to this part are specific national/regional/local considerations. Subject-oriented material such as the informed consent form, subject information leaflet, questionnaires, diaries, etc not only need to be in lay language but also in the local language. Given the various languages spoken in Europe, we assist our clients in drafting such specialised material depending on the location of the clinical study being planned.

In conclusion,

an appropriately designed study is the fundamental process through which a

research hypothesis could be translated into meaningful conclusions. In the

next chapter, we will discuss how to evaluate feasibility of conducting

clinical studies and how ACT as CRO complements its clients with their clinical

investigation programmes.

[1] https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/resources/trends

[2] Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest. 1989;95(2Suppl):2S-4S.